Le Centre d’Art is among the oldest surviving cultural organizations in the Caribbean and serves as a gallery and museum, an art school, and a site for art events and a meeting place for Haitian artists. It was established in 1944 by the American watercolorist DeWitt Peters, who served as its first director, and a group of Haitian intellectuals and artists that included the Indigenist writer Philippe Thoby-Marcelin and the architect and artist Albert Mangonès (who created the famous statue of The Unknown Maroon, 1967, in Port-au-Prince). Le Centre d’Art was in 1947 recognized as an “institution of public utility” by the Haitian state and the artists who have been associated with the Centre over the years include such well-known Haitian artists as Hector Hyppolite, Philomé Obin, Jasmin Joseph, Rigaud Benoit, Wilson Bigaud, Préfète Duffaut, and, more recently, Edouard Duval-Carrié, Lionel St Eloi, Mario Benjamin, and Tessa Mars.

In its early years, Le Centre d’Art was a cosmopolitan meeting ground for artists, critics, curators, and collectors from Haiti and elsewhere in the Caribbean, Europe, and North America, and served as a place where seminal ideas about modernism, popular culture, and Caribbean art were being explored and articulated. It is important to recognize this, since modernism is often misrepresented as an artistic movement with which places like the Caribbean had only a secondary, derivative relationship, while the region played a far more active role.

The Cuban art critic and curator José Gomez Sicre, who later became the director of the OAS’ Art Museum of the Americas, visited in 1945. The French Surrealist André Breton and Cuban painter Wifredo Lam also came to Haiti during that year and Lam had an exhibition at Le Centre d’Art in 1946. Le Centre d’Art also had an active working relationship with Alfred Barr and René d’Harnoncourt, the early directors of the Museum of Modern Art who were also advised by Gomez Sicre, and from 1944 onwards, several major Haitian works were acquired through Le Centre d’Art for the MoMA collection (whose early acquisition program also include work from Mexico, Cuba, and elsewhere in the Caribbean and Latin America).

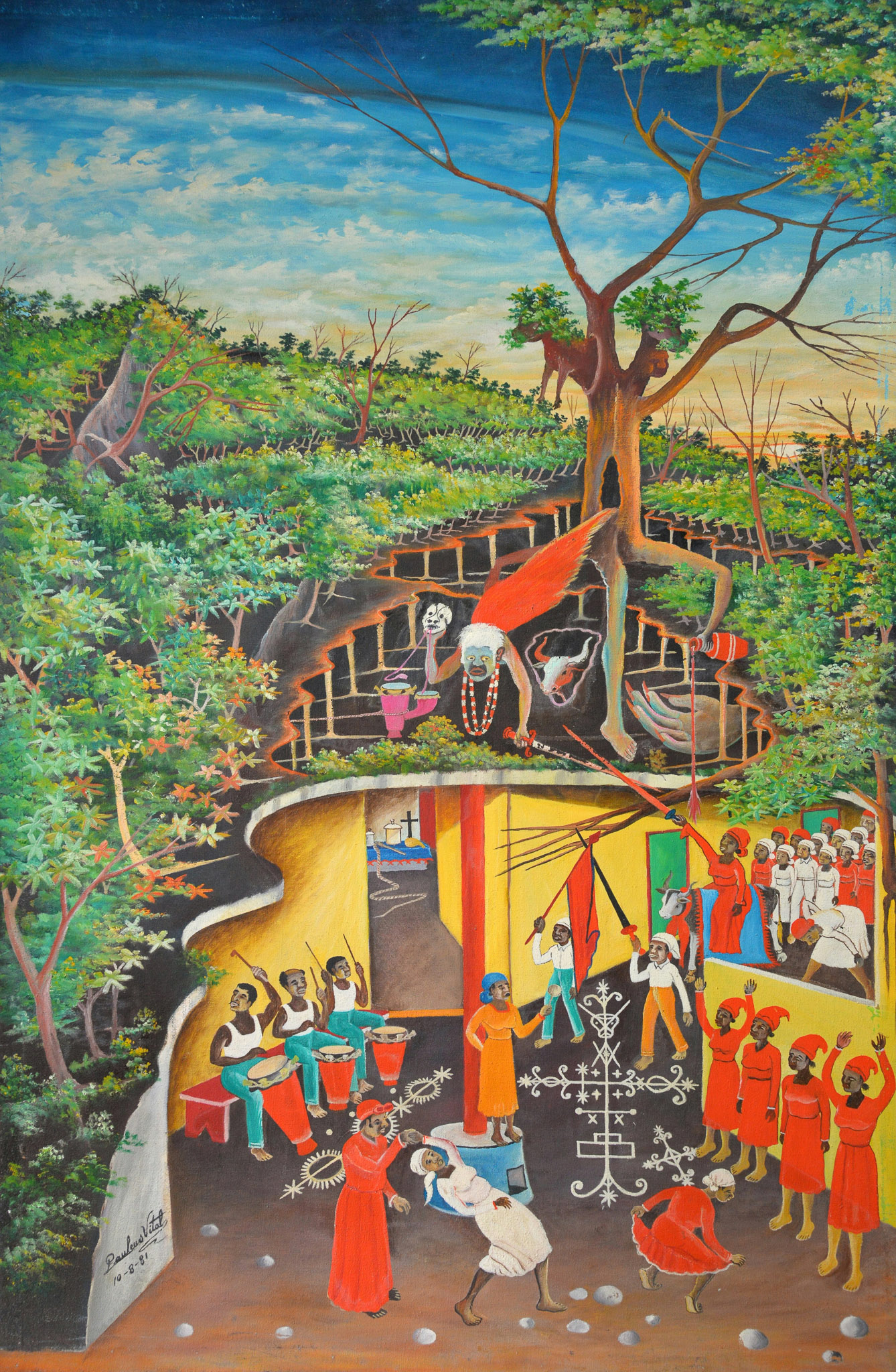

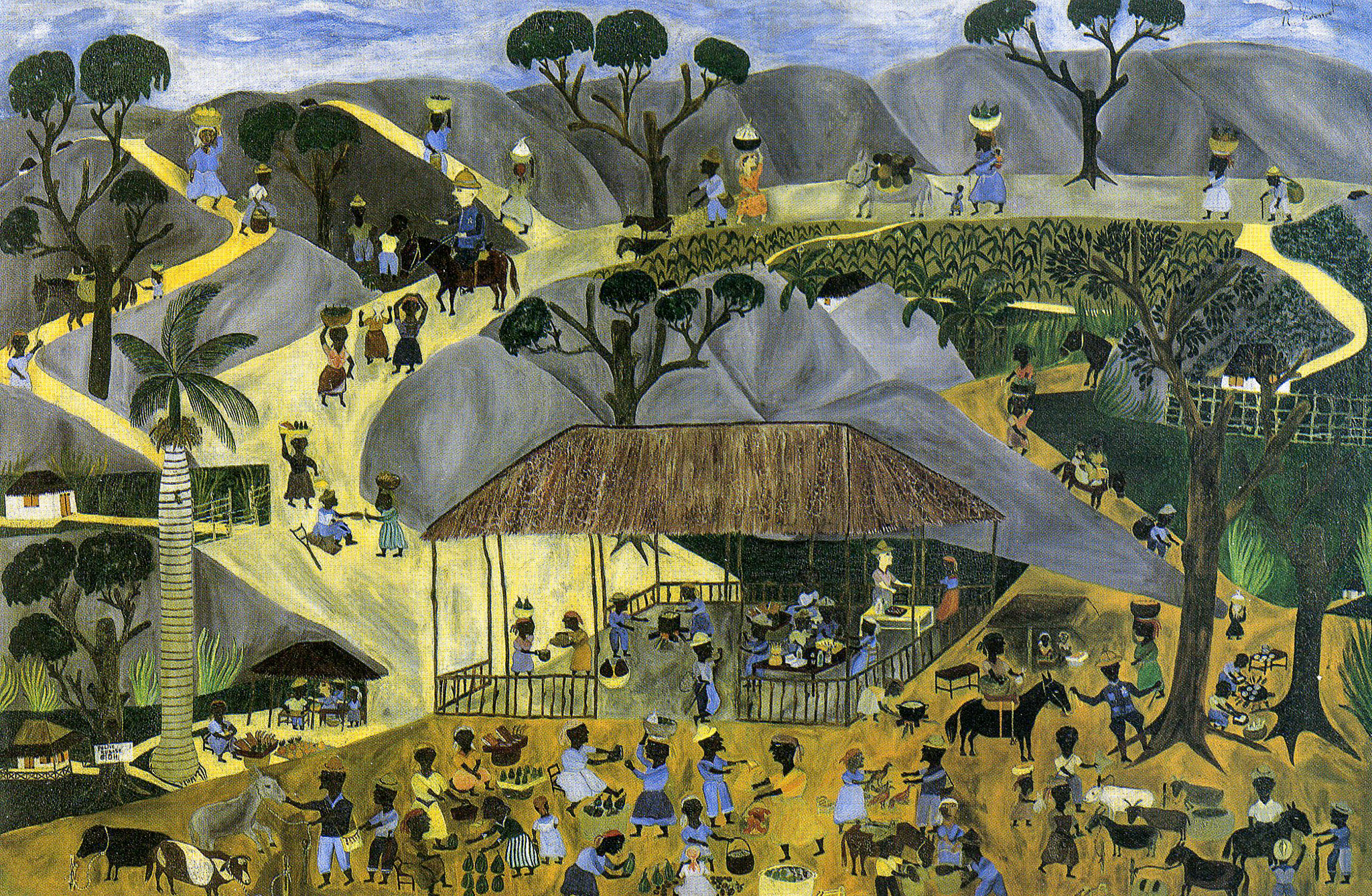

DeWitt Peters and the American critic, poet, and collector Selden Rodman, who became involved in the late 1940s, very enthusiastically engaged in talent-scouting, especially of popular, self-taught artists. They were, however, as some of the critics have argued, perhaps too actively coached to pursue a particular aesthetic and subject matter, as could be seen in the murals of the Holy Trinity Cathedral, which was a project instigated by Le Centre d’Art. Peters and Rodman have been credited with the “discovery” of artists such as Hyppolite and Obin, and there is no doubt that they were instrumental in placing these artists on the international art world map, but several of their “discoveries” were already active before they joined Le Centre d’Art.

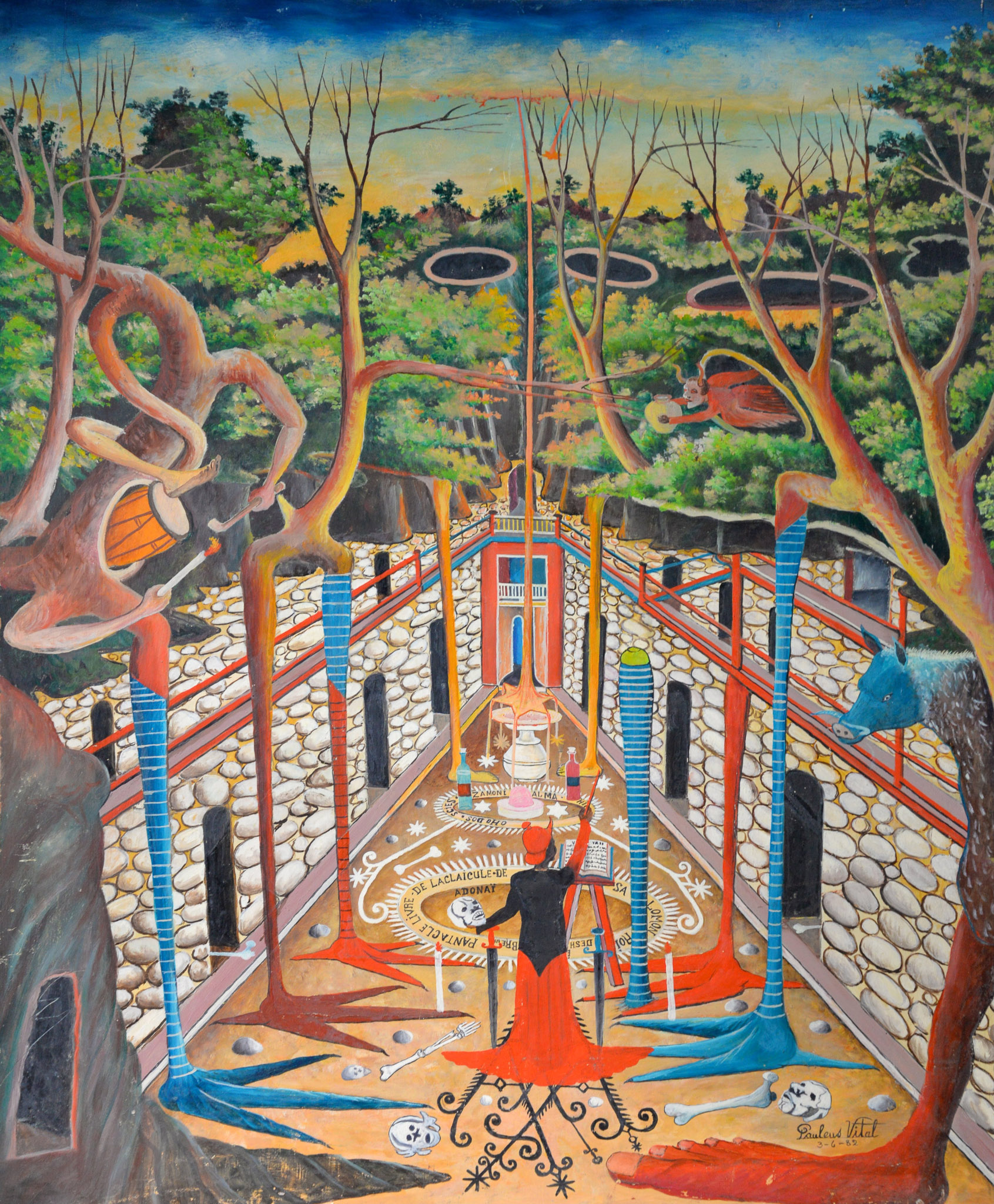

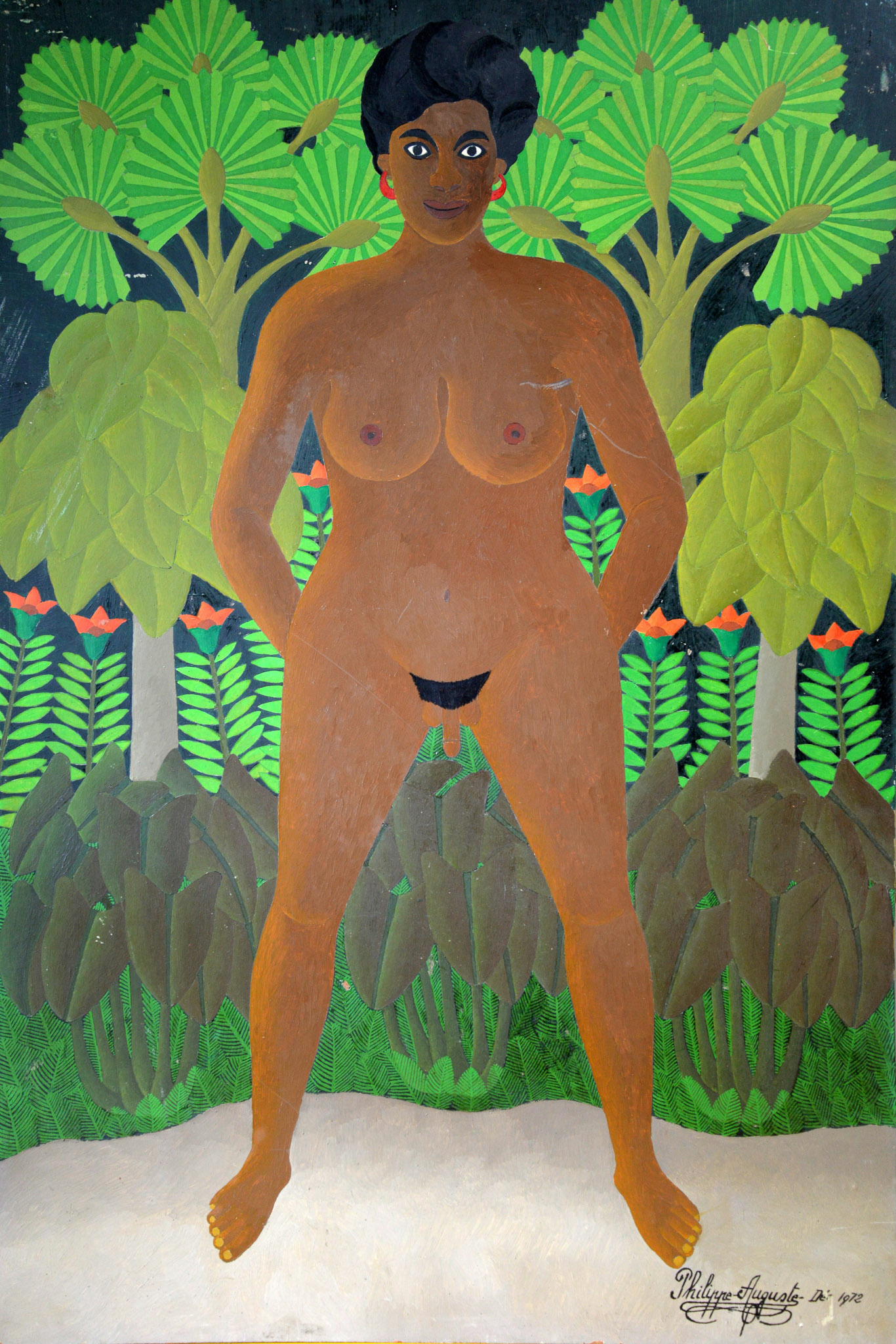

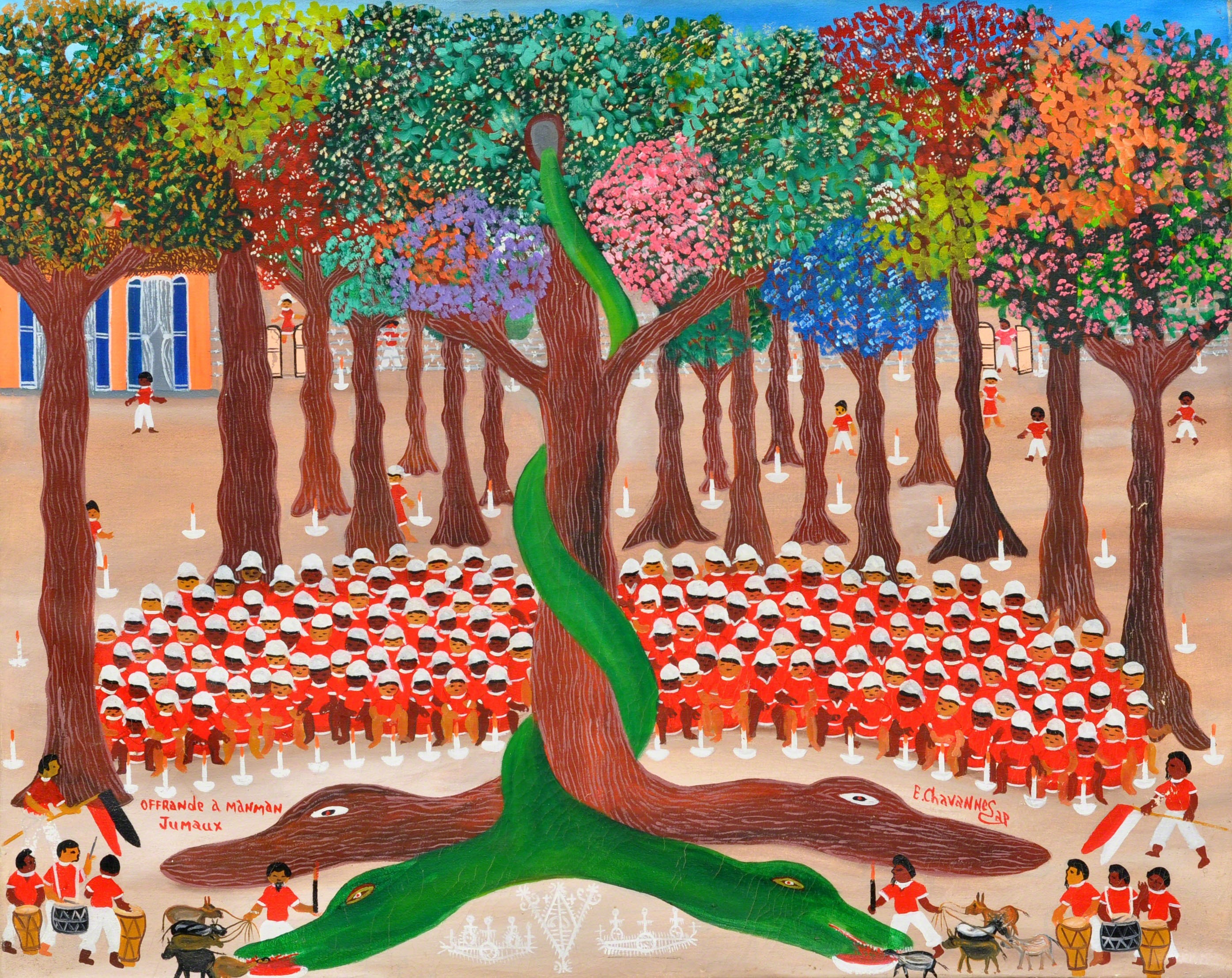

Selden Rodman’s widely circulated 1948 book Renaissance in Haiti: Popular Painters in the Black Republic not only supported the international breakthrough of the so-called Haitian School but promoted the idea that this school was a cultural miracle, a sudden spark that somehow emerged spontaneously from the substrata of popular creativity, fueled by Vodou culture. Even more problematically, it introduced the notion that the only true and legitimate Haitian art was the so-called Primitive or Naïve art, which was a stereotypical representation of black, Caribbean art with which many in the Haitian art world and intelligentsia were deeply uncomfortable, more so because it was championed by two white, American expatriates. The history of Haitian art is a much longer and complex story which should at least go back to the Haitian Revolution, and arguably earlier, and which includes popular as well as academic expressions. It was inevitable that this reductive narrative would be challenged.