Postcard From Haiti: September 2024 by Rick Forgham

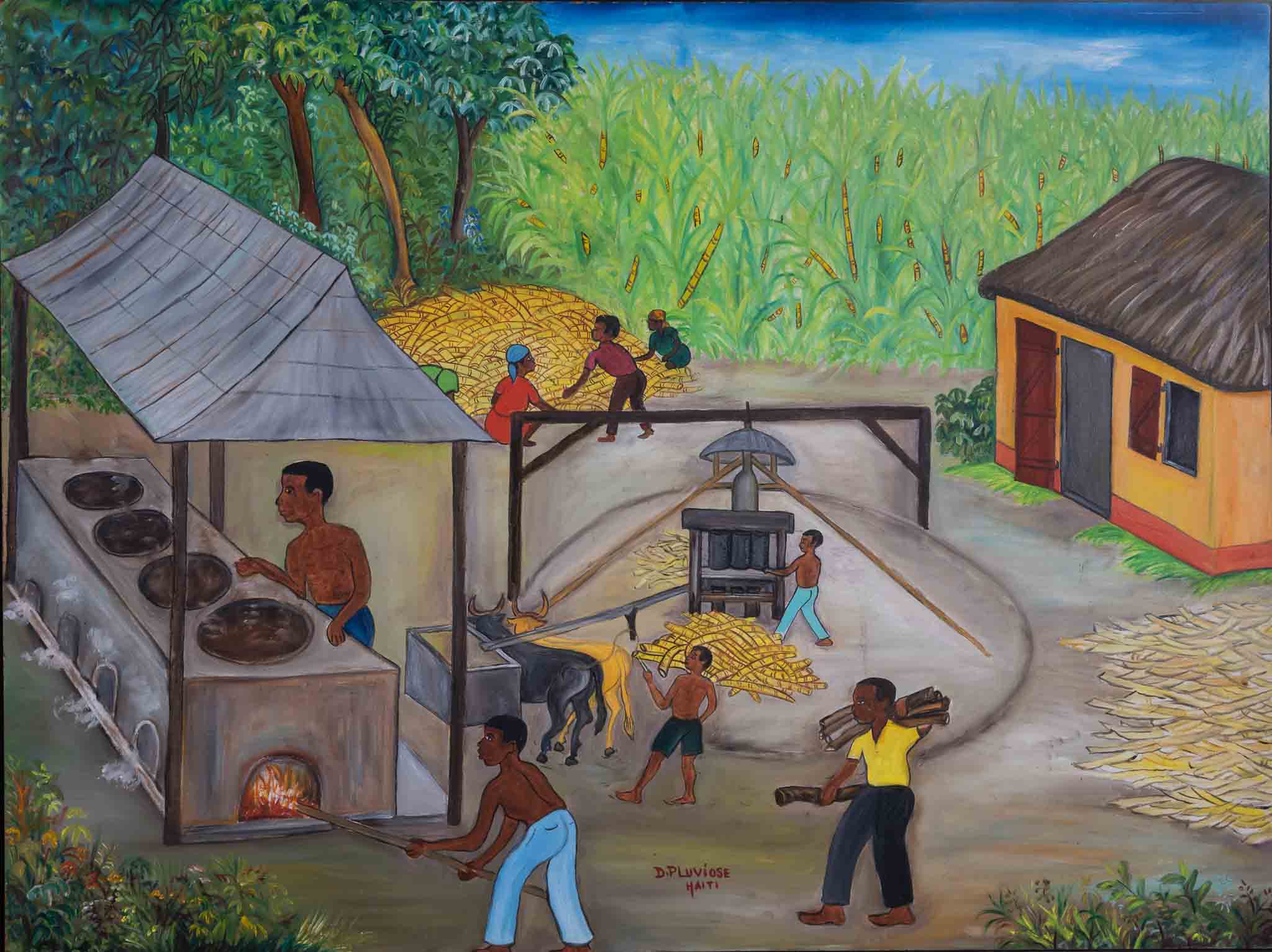

The story of September’s Postcard from Haiti is based on a wonderful painting by Dieudonne Pluviose that depicts the process of making Rapadou which is Haiti’s artisanal sugar. Rapadou is still made to this day in the time-honored fashion as shown in the painting. The process has changed little since the colonial period when Haiti was known as Saint Domingue. The artist has included everything that goes into the making of Rapadou. The verdant field of mature sugar-cane in the background, the cut stalks being cleaned and sorted prior to crushing, the canes being fed into the animal-powered crushing wheels, the juice flowing down a trough and into a small reservoir, and finally, the boiling shed where the sweet sugar-cane juice is reduced until it crystalizes and becomes Rapadou. This unrefined sweetener that not only has a robust flavor, but a helping of Haiti's history and traditions is all packaged in a palm leaf wrapper.

Sugarcane was never native to Haiti, Hispaniola, or any of the Caribbean islands, so how did it get there? The story begins when a grass known by botanists as Saccharum Officianum was first cultivated on the African Continent in the area currently known as New Guinea some 10,000 years ago. This grass, which we now call sugarcane, was prized due to the number of uses that were developed many thousands of years ago for its sweet juice. Because of its popularity as a producer of sweeteners, the grass eventually spread eastward to India, Thailand and Indonesia. Later it spread westward across the Atlantic and all the way to the Canary Islands. Then in 1493 while starting out on his second voyage, Christopher Columbus and his fleet of ships stopped in the Canaries for supplies. While there he invited several sugar-cane farmers to join the expedition, and the growers brought with them a supply of their prized plant stock. These first canes were eventually planted in the fertile soil of Hispanola and in the ensuing centuries the “sugar rush” would come to replace the search for gold throughout the Caribbean.

While growing up in Haiti my best friend Philip Mongeau and I would ride our bicycles out into the countryside outside of Port-au-Prince and on more than one occasion we visited scenes such as the one in the painting. In 1957, when we were both just eleven years old, Philip used his Kodak Brownie camera to take the photo below of an animal-powered sugarcane crushing mill that we came upon in Croix-des-Bouquets, about ten miles northeast of the capitol. This particular mill was not in operation on the day that Philip took the photo, but other mills we visited over the years were often running full-tilt. The sweet aroma of boiling sugar-cane juice would fill the air and we would watch as the steaming liquid would be transferred from pot to pot down the line as the syrup became thicker. Once the syrup in the final pot reached the proper viscosity the liquid would be ladled into palm leaf molds to cool and eventually crystalize into circular cakes. After hardening these cakes, which are called “Kayet”, would be taken to market and sold.

Over fifty years later the steps that are taken in making traditional Haitian Rapadou remain essentially the same as illustrated by Pluviose in his painting. The only part of the process that has been modernized since the 1970’s would be the replacement of the slow animal-powered mills by diesel-powered sugar-cane crushers that have greatly speeded up the crushing part of the process. Haitian Rapadou remains the same, a delicious natural sweetener possessing complex caramel and molasses flavors that can magically add a subtle dose of Haitian sunshine to your coffee, desserts and beverages.

Enjoy!

Rick Forgham September, 2024