Postcard From Haiti: October 2024 by Rick Forgham

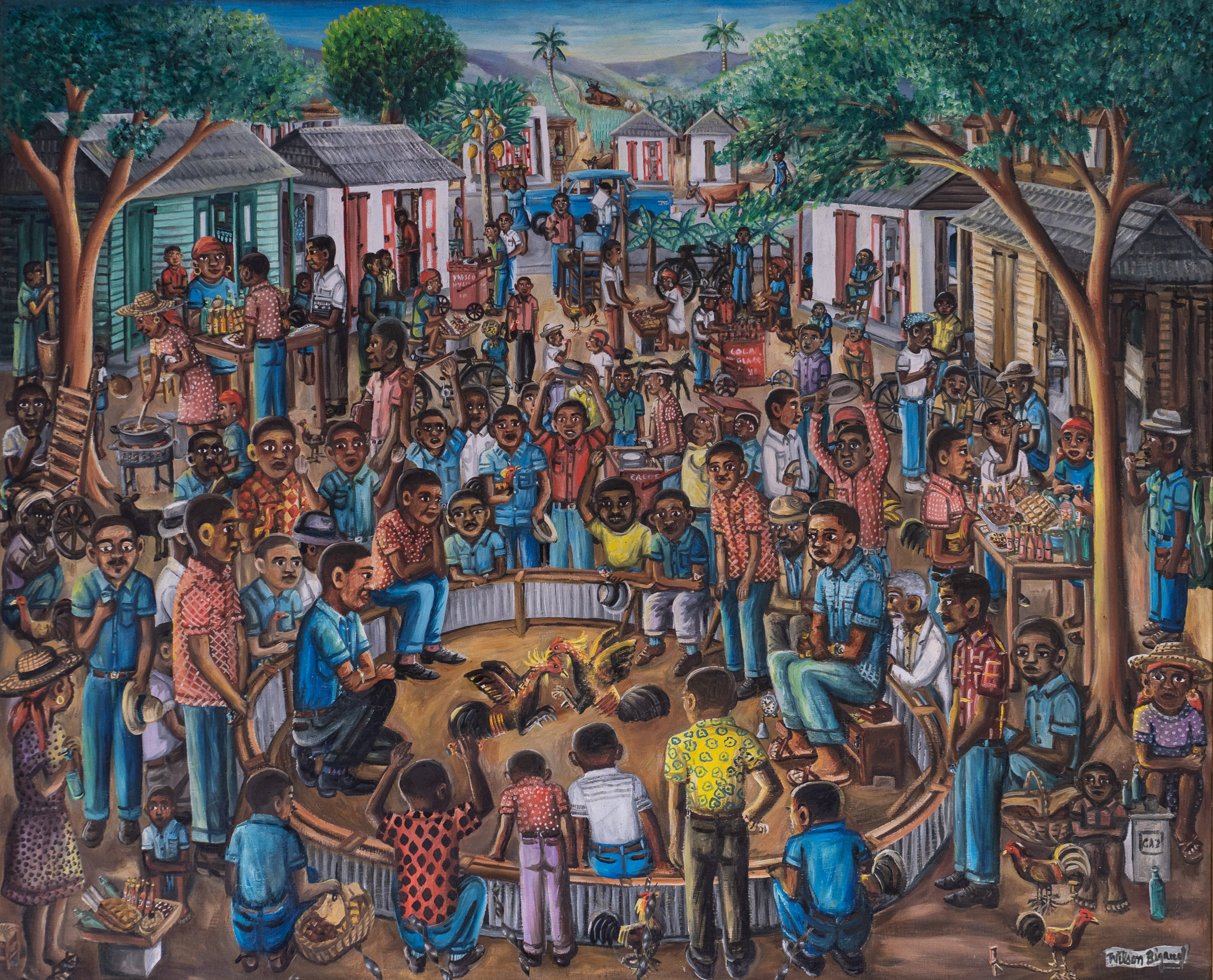

Throughout rural Haiti a popular Sunday afternoon event is the gaguere, or cockfight which usually takes place in the central area of a village or town. In this painting done in the 1970’s by Wilson Bigaud all the excitement and socializing that takes place is laid down on canvas. The cockfight has been painted countless times by Haiti’s artists as the event is part of the fabric of Haiti. I must mention however that the spectacle can become gory and is perhaps not for everyone.

But back to the village scene before us. Bigaud has opened a window onto a village and captured so much of what one would see at a Sunday afternoon gaguere. Towards the top of the painting, just below the blue car, there is a Ticket Desk where attendees pay a modest entrance fee. There are vendors of all sorts selling refreshments and food to the crowd. A woman is frying up acra patties over a charcoal brazier while the “Fresco Hygenique” man with his cart is shaving snow-cones which take the edge off the heat of the afternoon. Another cart is offering “Kola Glacee” or cold soft drinks.

A man on the left is cradling his transistor radio so that he can receive the results of the Sunday afternoon lotteries in the Dominican Republic and Venezuela. The outcome of these foreign lotteries will determine if the borlette ticket he purchased earlier will be worthless or perhaps a valuable little slip of paper that will yield a payoff when he redeems his winning numbers. Prized fighting cocks are everywhere in the painting. There are at least eight visible, some tethered to a small stake in the ground and others are held under the arm of their owners. Not all will be combatants today as some owners simply enjoy bringing their prized birds for show or perhaps to challenge another bird owner to a future match.

Bigaud uses the corrugated metal ring which forms The Pit to focus our attention on the action that is taking place at the moment. Two roosters are engaged in what appears to be a fierce battle. All the bets have been placed and are securely locked in the cabinet in the stool that the pit’s “Controller” is seated on. Each match is timed to thirty minutes, and he is keeping track of the time with the clock at his feet. If both roosters are still going at it at the end of the allotted time the arena judge will declare a winner. He is the fellow kneeling to the left of the battling cocks who is intently observing their skirmish.

The novelist Herb Gold who has written much about Haiti gives this account of a man whose bird did not prevail one Sunday.

His bird has just had its eyes pecked out and its skull fractured. This expensive, highly trained, meat-fed battler upon which he has lavished so much love is now good only for the frying pan. He accepts the glass of consoling rum, but shakes off the sympathy of his friends, wiping his eyes with his sleeve and crying out: “Listen, you!” (A hush comes over the huddle of men. ). “Listen, let me tell you what has happened to me, otherwise you will not know. I came with my cock in a sack to win lots of money. I promised my girl a trip to Le Cap. You know what women are. Well, I spread this cock’s wings, and I sprayed it with rum and I licked its beak in mine and I bet everything I had. My old father’s money too! My cock fought, friends, it lost, yes, you know it, but I don’t go home empty-handed, not me. No, dear friends, I still have the sack!” With the roar of laughter and applause that rewards him, he is no longer defeated. All of these men have lost and know what failure means. He has communed with them. He has made a work of art of his defeat and therefore a triumph.

And so would end a Sunday afternoon in a rural village somewhere in Haiti in the 1970’s as faithfully depicted in this painting by one of Haiti’s foremost artist-storytellers Wilson Bigaud.

Rick Forgham October, 2024