Meet the Papa Zaka(s)

Papa Zaka or Cousin Zaka is the patron loa (lwa) of agriculture and farmers.

Other notable loa or spirits include Papa Legba (guardian of the crossroads), Erzulie Freda (the spirit of love), Simbi (the spirit of rain and magicians),

and the Marasa, divine twins considered to be the first children of Bondye from the French (Bon Dieu = Good God).

In the paintings by Gerard Valcin, Papa Zaka is barefoot. He is smoking a pipe and wearing blue denim, a straw hat and smoking a pipe.

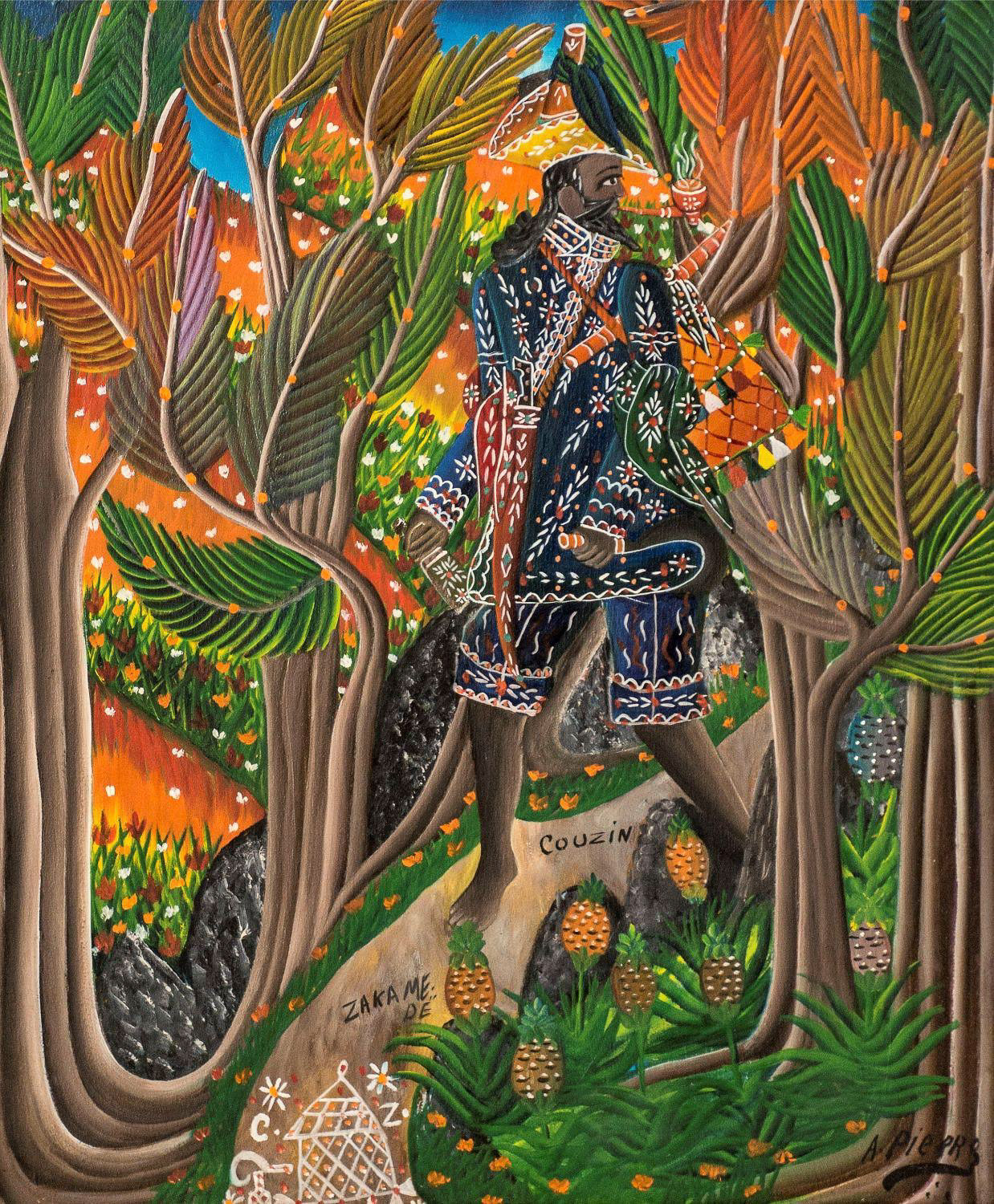

In Andre Pierre's painting of Kouzen Azaka, he is also barefoot. Kouzen Azaka sports a hat, holds his pipe and has his "makout" bag on his shoulder.

From Robert Farris Thompson, in the book Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou:

Papa Zaka, patron of agriculture, walks strongly. Tasseled bag and pipe “name” his motion, name this good-natured man of the mountains. His garb is that of a peasant: sturdy blue denim, straw hat, and bag; that’s why the chromolith of St. Isidore evokes “Kouzen” Zaka.

Zaka's bag is a document of Creole ingenuity, encoding the cultural collision of Vodou and the Spanish element on the island of Hispaniola. At some point during Spanish rule, Haitians absorbed the Iberian straw knapsack, called alforja in Spain and alforge in Portugal; they changed its name to alfo and changed its shape as well. Compare an early 20th-century alforge, from Monchique in the Algarve, north of Portimao, to Zaka’s bag. The Iberian object reads with visual forthrightness: straw structure, red fabric trim, two tassels at the bottom, and a frontal design in red and black. Zaka’s alfo, though also made of woven straw, with red trim and dark tassels at the bottom, is more than a knapsack.

Zaka’s alfo is a divine signature, part of the dress of the Haitian farmer god. The Creole synonym for this bag, makout, introduces another intersecting line of influence. Makout derives from Ki-Kongo, nkutu, “small cotton bag carried on the shoulder.” The Kongo medicines of God include nkutu amooyo (lit. spirit-bag), or as Laman put it, “the name of an nkisi for guarding one’s life” (1936, 2, p. 737). Memories of such objects, kept alive in speech, would explain a critical difference between the Iberian version and the Haitian one: the latter can be covered with a lattice of knotted cord, like a whole class of nkisi bags in Kongo (cf. McGaffey 1993, pl. 43). Lattice-work is a powerful element of Kouzen Zaka’s vévé. The rhythmically repeated tassels, plus the pipe that Zaka loves to smoke, set the alfo apart as a sacred object. The alfo is thus written over with intensified notations of motion (the tassels) and pleasure (the pipe).

Cosentino, Donald. Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 1995.

According to Andre Pierre: (translated from Creole)

Cousin Azaka, Minister of Agriculture. In the Catholic Church, it is equivalent to St. Isidore who walks with Granny Ibo. He controls agriculture in order for the land to prosper. Whatever is connected with the earth goes through Cousin Azaka. The earth is under his command. Human life is controlled by Azaka.