oil on masonite

24'' x 16''/ 61 x 41 cm.

Framed: 25'' x 17''/ 64 x 43 cm.

Provenance: Jonathan Demme (according to Jose Zelaya, this painting hung in Demme's home office)

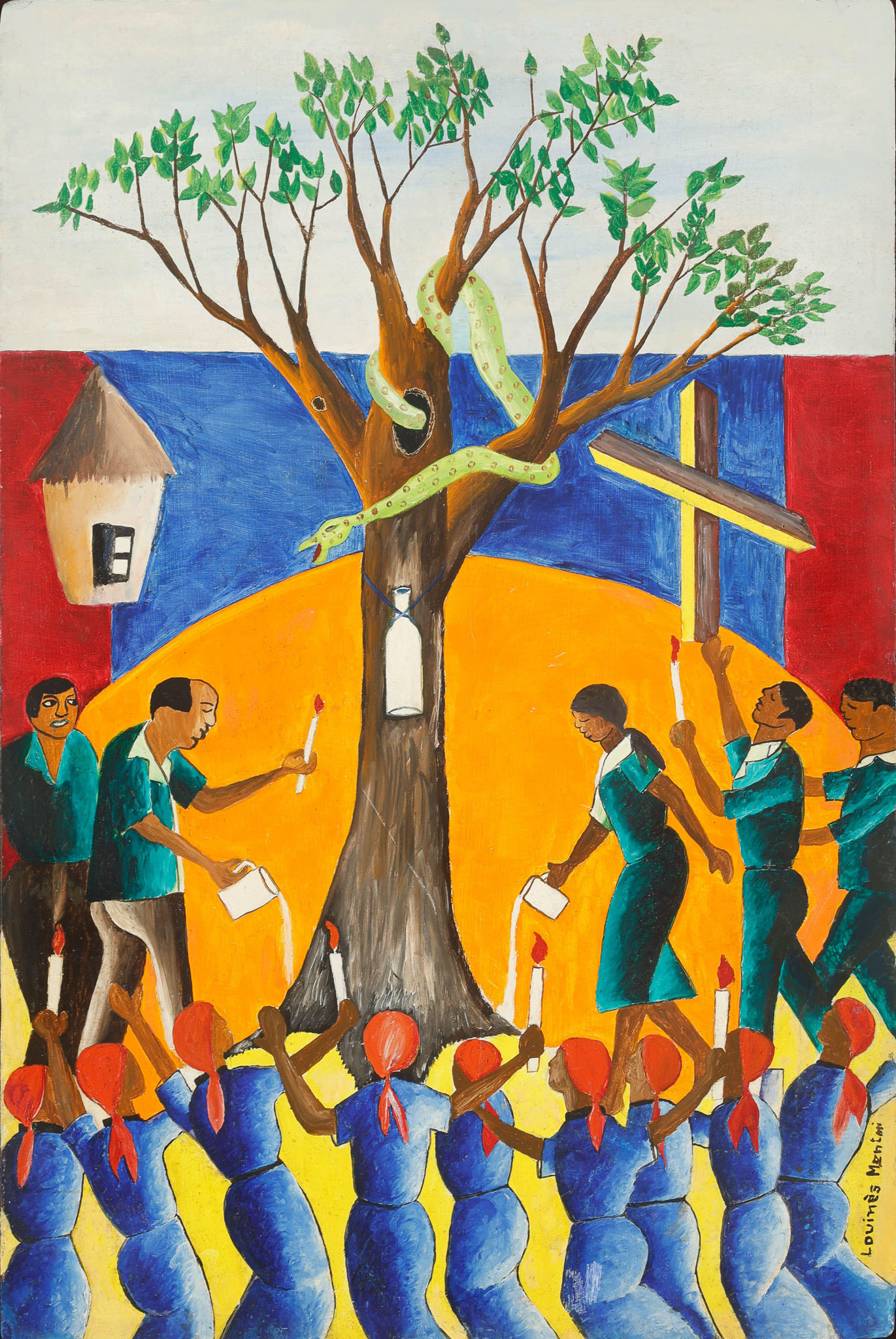

This vibrant painting is a visual hymn to one of Haitian Vodou’s most ancient and powerful loas (spirits): Damballah (sometimes called Damballa Wedo), the great cosmic serpent. Several elements in the composition point to this reading:

The Snake Winding Through the Tree

In Vodou cosmology, Damballah is often envisioned as a primordial serpent who coiled around the world‐tree at creation, shaping the landscape and bringing order out of chaos. Here the green, spotted serpent loops through the branches, its head almost touching a hollow in the trunk—an unmistakable reference to Damballah’s shelter in the arboreal realm and his role in animating all life.The Tree as Axis Mundi and the Poto Mitan

The sturdy trunk, rising from dark soil into leafy boughs against a two-toned sky, functions as the Vodou axis mundi—the sacred center that links the underworld (the roots), our world (the trunk), and the heavens (the canopy). In Haitian temple architecture, this concept is embodied by the poto mitan, the central wooden pillar around which the ritual space revolves and through which the loas descend into the congregation. Here, the painted tree serves that very role: it is both the cosmic pillar and the poto mitan of the scene, grounding the community’s ceremony while channeling Damballah’s presence up from the fertile earth into the spirit realm.Milk Offerings and Libations

Notice the white jugs held by the men and the milky fluid being poured down the trunk. In Vodou ritual, one common offering to Damballah is pure, fresh milk. Pouring it at the base of the tree is a libation that “feeds” the loa, inviting his presence and his blessings of health, rain, and prosperity.Candles, Crosses, and Syncretism

The candles raised by both the standing figures and the kneeling circle of women symbolize the light that guides the loa down into the ritual space. The wooden cross on the right—while instantly reminiscent of Catholic iconography—is also a syncretic nod to Papa Legba, the crossroads guardian who must be petitioned before any other loa can be approached. This interweaving of Christian and African symbols is at the heart of Haitian Vodou’s resilience and adaptability.Communal Devotion

In the foreground, a group of women in headscarves kneel in unison, arms uplifted with candles. Their red scarves may allude to the fiery Rada-Petro divide (red for the more assertive “Petro” spirits), but here they also underline the collective energy that powers every Vodou ceremony. Around the tree, both men and women work together—lighting, pouring, praying—reminding us that Vodou is as much about community bonds as it is about individual communion with the divine.Color Symbolism

The vibrant yellow circle behind the tree could stand for the sun or for the brilliant light of the spirit world shining into ours; the deep blue and red flanking it recall the colors of the Haitian flag, subtly rooting this ancient practice in the nation’s own struggle for freedom and identity.

Louines Mentor’s vodou painting is not a mere still life or genre scene but a living depiction of a Vodou rite of invocation and thanksgiving. It shows a community united in ritual, reaching across the thresholds of earth and sky, human and divine, in order to commune with Damballah—seeking his life-giving waters, his protective wisdom, and the very spark of creation he embodies. by Matt Dunn